Memphis Grizzlies point guard Mike Conley comes from a family of world-class athletes.

His father, Mike Conley Sr., was an Olympic gold and silver medalist in the triple jump, while his uncle, Steve Conley, was a linebacker for the Pittsburgh Steelers.

As a child, though, the younger Conley was keenly aware that not everyone in his family was so blessed when it came to health.

Two of his cousins suffered bouts of debilitating pain and frequent illness because they were born with sickle cell disease, a genetic disorder affecting approximately one in every 500 African-Americans.

“It was hard to see my family struggle off and on with sickle cell. Growing up it was tough knowing what they were having to deal with, so I thought I would try to help as best as I could,” Conley says.

As a Grizzlies star, he has lent his time, money and celebrity to supporting Methodist University Hospital’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center in Memphis.

Just before the start of Grizzlies training camp each year he hosts the Mike Conley Bowl-N-Bash to raise money and awareness.

Sickle cell center pioneers new model of care

The Methodist University Hospital’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center is making the present better for its patients by helping them manage their disease.

As for the future, the center is a research partner with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, participating in work that may lead to a cure.

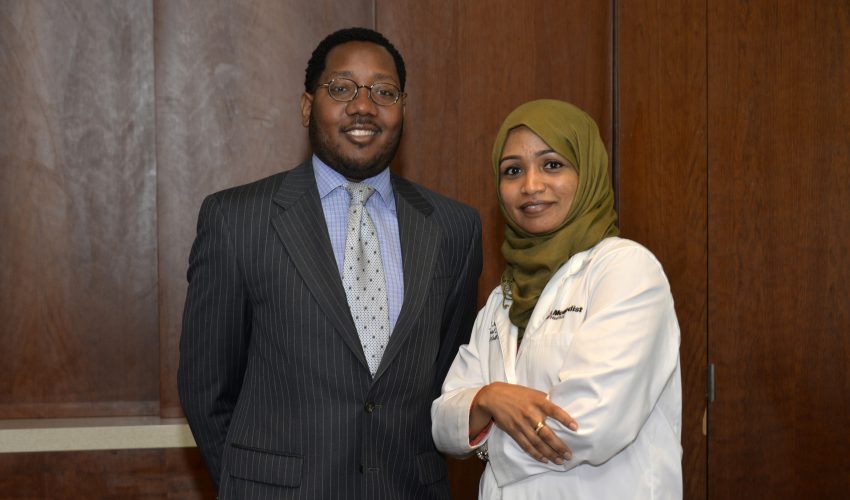

“Because it is caused by a faulty gene, people are born with sickle cell disease and will suffer with it their entire lives,” says Dr. Nada El Magboul, who until recently was the primary care physician for patients at the Sickle Cell Center, which opened in 2012 following a $3 million fundraising campaign.

In addition to having normal blood cells, those with the disease have other cells that are misshapen “like a banana,” El Magboul says, and do not flow as smoothly through the blood vessels.

This shape leads to clots, which cause excruciating pain when tissues nearby are starved for oxygen.

Prior to the opening of the center, Methodist University was treating sickle cell cases in its emergency rooms and then admitting patients for an average of six days of treatment, according to Mark Yancy, director of the center.

Mark Yancy, Director of the Methodist University Hospital Sickle Cell Center, and Dr. Nada El Magboul

“We saw there was a better way, by creating a medical home model, where their care is coordinated in one place,” Yancy says.

Through the center, nearly 200 sickle cell disease patients have a primary care physician.

When they know an attack is underway, they can go to the center for treatment with intravenous fluids and pain medication, easing the crisis.

And they can usually go home the same day, Yancy says, reducing both stress and cost for patients.

By becoming part of the center, patients learn ways to help prevent attacks. Drinking plenty of water, for example, is more important for people with sickle cell disease, because dehydration is a common trigger for clots. Emotional stress is also a trigger, and patients learn ways to reduce anxiety.

In addition to being a research partner with St. Jude, Methodist University’s Sickle Cell Center also has a clinical partnership. Pediatric sickle cell patients of St. Jude are offered a smooth transition to adult care at the Methodist University center.

Promise for the future

Research has made treatment better for people with sickle cell disease. For instance, hydroxyurea is a cancer drug that also reduces the number of sickle cells, reducing the frequency of clots, and has become a standard treatment.

In some cases, bone marrow transplants can eliminate the disease, but the number of patients where transplantation is an option is small because donor matches are hard to come by.

“Because sickle cell disease is genetic, hope for a cure lies in discovery of a gene therapy that can transform the patient’s genes and remove the trait,” El Magboul says.

Working toward that cure, Methodist University Sickle Cell Center has entered into a resource-sharing agreement with St. Jude that has expanded the number of clinical and research staff.

“Sickle cell causes a great deal of suffering and it would be a great day when a cure is discovered,” Yancy says.

“When I encourage people to support sickle cell care and research, I just tell them a little bit about the disease and how many people are affected by it. Ultimately, I’m trying to raise more awareness and money to be able to help combat the disease in the future,” says Conley.