Substance abuse is often seen as a victimless crime — the person being hurt most is the user. Pregnancy changes the equation.

Drug use can damage an unborn child in ways the mother never imagined.But a pregnant woman taking drugs takes a lot of risks if she admits to the problem. She could be arrested. Her baby could be taken away. She could lose her job. And no matter what else happens, she will undoubtedly find herself facing harsh judgment from others.

“We’ve seen higher doses and stronger medications being used by women during pregnancy. It was just shocking and depressing to see.”

That, says Dr. Geogy Thomas, medical director of Dayspring Family Health in Jellico, Tennessee, is the toughest hurdle his clinic faces in trying to help these young women.

“Our greatest issue is getting over the stigma of drug abuse,” he says. “The truth is that it is here and it involves every aspect of our community. Some will push it off as a problem of the poor, but we see it affecting every social strata, from the poor to teachers to bank presidents.”

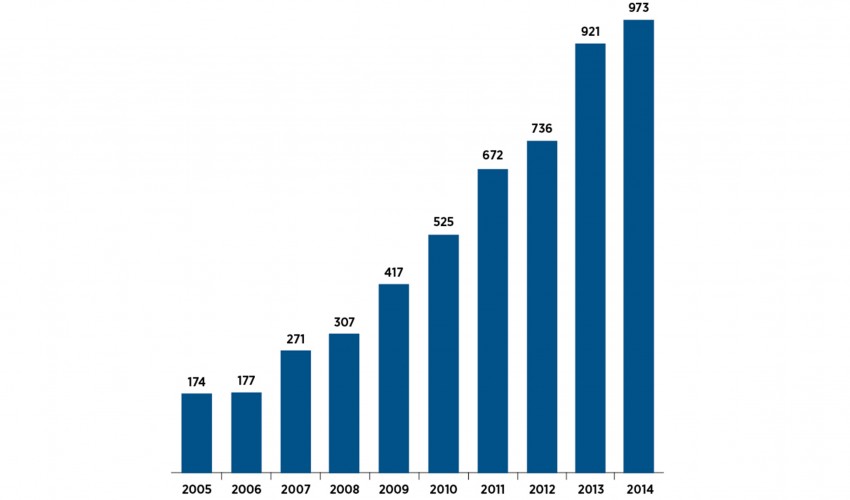

And since Dayspring Family Health serves an area of Tennessee with an alarming rate of substance abuse, it is also seeing a huge increase in the number of pregnant addicts whose babies are born with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. They become dependent on drugs in the womb, which causes them to suffer from withdrawal soon after birth.

The withdrawal process, horrific for an adult, takes an even more terrible toll on a baby. It is nearly impossible to comfort them, and the symptoms can last for weeks.

We have to do something

Dr. Thomas first arrived at Dayspring Family Health Center 15 years ago from Chicago and instantly fell in love with the area and its people. About ten years ago he and his colleagues noticed a spike in drug use in the area.

“We were just registering what was going on, but it really started hitting us when we saw OB patients coming in on drugs,” he says. “We’ve seen higher doses and stronger medications being used by women during pregnancy. It was just shocking and depressing to see.”

They began working with the University of Tennessee Medical Center’s High Risk Pregnancy department, but even at the highest levels of medical research, there was little agreement on how to treat the problem.

“It was a medical and ethical conundrum,” says Dr. Thomas. “And that’s when BlueCross BlueShield appeared at our door to offer help. They had seen the numbers and had traced the largest number of cases of NAS to our community. And so the question was, what do we do?”

Number of Inpatient Hospitalizations with Any Diagnosis of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome in Tennessee, 2005-2014

The answer: Mothers and Infants Sober Together (MIST), a six-month program designed to get expectant or new mothers off of drugs and in a position to care for their babies. Dayspring gave some space to MIST within the clinic walls and now refers its patients to the program.

“Our care manager, Loretta Phillips, is able to explain the need for help and engage our patients in a sweet and gentle way,” says Dr. Thomas. “She does the hand-holding to get the patient that next mile, enrolled in MIST.”

Dr. Geogy Thomas and Care Manager Loretta Phillips make sure mothers take important steps like ultrasounds.

Making the transition

As care manager for the clinic, Phillips offers guidance to patients with questions or specific challenges, and always meets with obstetrics patients at least once during their care. If it becomes clear that the expectant mother has a history of substance abuse or is currently using, she lets them know about MIST.

By building trusting relationships with Dayspring’s patients, Phillips is often able to overcome a drug user’s natural inclination to resist help. She makes it clear that they are in a supportive place, where nobody is judging them and nobody wants to take their baby away from them. Sometimes, finding the right way to deliver that message takes a bit of luck and ingenuity.

“Recently I spoke to a young mother whose NAS baby was in the hospital. She was very sweet, but not ready to commit to the six months that the MIST program requires,” Phillips recalls. “It happened that a patient who had graduated from MIST was in the building, so I asked her to come talk to this young woman.”

“We know it’s a difficult journey, and we give them chances to come back if they fail a drug screening.”

Hearing from someone who had been there did the trick. And being able to walk down the hall and make a personal introduction to the MIST counselor right then and there ensured follow-through.

“It’s one thing to hand someone a piece of paper with instructions to join a program,” says Phillips. “But when I can say here’s the paper you need and here’s the person to talk to, well that’s huge.”

Care Manager Loretta Phillips encourages young mothers to enter the MIST program.

Doing the work

The six-month commitment allows the behavioral health work to align with the physical detoxing from drugs.

It takes around three months for a drug abuser to mentally get past their addiction and up to a year to stop craving the high.

“We know it’s a difficult journey, and we will give them chances to come back if they fail a drug screening,” says MIST director Michelle Jones.

Ideally, women come to MIST while they are pregnant, but most make the commitment after their baby is born and they can see the connection between their behavior and their child’s condition. Once they join, the women go through a thorough evaluation of their drug history and personal background. They are then invited to join the weekly group therapy sessions, in addition to attending individual therapy and connecting with a case manager, who meets with them in their home regularly.

“Having our case manager work with the client in the home is a big part of the program because we want to see what the home life is like to help change some of those cycles — like difficulty parenting or domestic abuse — that may contribute to drug use. Seeing what is happening firsthand is very beneficial,” says Jones.

There are videos to watch, parenting skills to learn, homework to do and serious self-examination day after day after day. The women who go through the MIST program make that effort so they can eventually be good mothers to their children, to be an example.

“I have learned so much from these women,” says therapist Kristen Kakanis. “The biggest struggle they face is one that so many of us face – the idea that they should be able to do this on their own. It takes a lot of strength to admit weakness and ask for help.”

Kristen Kakanis, therapist, is often inspired by the strength of the women she counsels.

That’s especially tough in a tight-knit community like Jellico. The everyone-here-knows-each-other small town culture often turns into an obstacle for new enrollees when the prospect of group therapy comes up. They worry that they will run into somebody they know, and word will spread. But eventually even the wariest mothers warm to the give and take of these sessions.

“At first they are scared and don’t want to talk,” says Kakanis. “But this is a safe, confidential space for them, and they are surrounded by women who have been where they are. Once they open up, they will share very personal, deep emotional things.”

Getting to that core, their reason for depending on drugs, allows the women to change their behavior. Some have been using drugs since they were just 12 years old. But now there is a little person who is depending on them, and they do the work to be there for their baby.

“When we first meet these women, they are stoned or don’t care or are trying to hide something and refuse to talk,” says Dr. Thomas. “When you see these moms wake up from that drug haze, it’s beautiful.”

Kristen Kakanis and Michelle Jones, director of MIST, keep the door open to graduates of the program who need further advice.