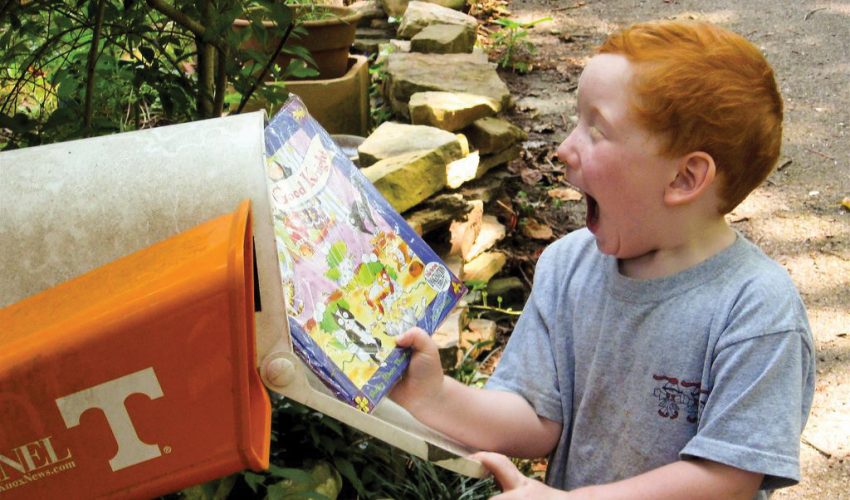

Children impatiently wait for planted seeds to germinate and sprout.

Recent parolees develop new skills in a kitchen.

Refugees break ground on gardens that will provide them a source of income.

Food is more than what’s for dinner in Tennessee communities, thanks to organizations that see healthy living as an unending harvest.

Children Learn by Playing in the Dirt

The Kitchen Community plants seeds that produce abundant rewards

Connecting children to gardens is the main thrust of the Kitchen Community in Memphis, which works with Shelby County Schools and Jubilee Catholic Schools Network on 50 gardens.

The hope is to double that number, and all indications are that the interest and enthusiasm are there, says Lisa Ellis, regional director.

“If a school wants a garden from us, they fill out an application, put together a garden team and have a site,” Ellis explains.

“It has to be between 1,200 and 1,500 square feet, because our gardens consist of benches, beds and boulders so that people can sit and be in the space as well as plant and work in the dirt.”

The area becomes a mini-complex of 12 beds in three different sizes, planted two or three times a year with a rotating variety of crops.

Teachers are encouraged to incorporate garden-related lessons into curriculums on health, nutrition and math.

“The goal is to teach the kids about real foods, not to be a supplement for the cafeteria,” Ellis says.

“We want them to try, taste and grow new things, and then work them into their home lives.”

The organization has been in Memphis since April 2015.

After a solid first year, it’s on track to expand to 85 gardens by the end of the 2016-17 school year, and then add 15 more to meet demand.

“We have a new curriculum aimed to high schools,” Ellis says. “It will talk about gardening and farming with a career focus. We’re very excited about that.”

Teaching the teachers

At the same time, the Kitchen Community wants more teachers to feel comfortable incorporating gardening into their lesson plans.

The group assigns an educator to give one-on-one lessons to teachers and conduct workshops.

“The most popular one is on worm composting, where the teachers build a composter and take it back to their school,” Ellis says.

“Worms are a huge hit with kids, and along the way everyone learns some eco-responsible skills and habits.”

Most of the children do not have a garden of any type at home.

The school garden is a completely new experience, but once they’ve gone through the process from seed planting to harvesting, they’re hooked.

“Seeing them enjoy the fruits of their labor when they harvest is so much fun,” Ellis says.

“The best days are carrot days, because they don’t know how big it’s going to be until they pull it out of the ground.

“Their faces light up, and they get the connection between planting and caring for a garden and what you can get out of it.”

Feeding Many Types of Hunger

The Nashville Food Project collects food donations and encourages self-sufficiency with gardens

“Our mission is to grow, cook and share healthy food,” says Tallu Quinn, executive director of the Nashville Food Project.

“One in five Americans lacks access to enough healthy food.”

“We work with farmers markets, grocers, restaurants and caterers to recover an enormous amount of food so we can address that.”

That involves hustling around Middle Tennessee, collecting thousands of pounds of perishable foods, and then bringing it all to kitchens at Woodmont Christian Church and St. Luke’s Community House seven days a week.

Rather than redistribute the food as raw goods, staff and about 650 volunteers pair it with fresh produce from gardens the group operates to create from-scratch meals — about 2,500 a week.

“Our group of volunteers is getting more diverse by the day,” says Quinn.

“We have former meal recipients and people coming out of prison. Something amazing happens when they all come together around food.”

Food supplements other programs

Once prepared, the food goes out via 22 distribution partners, which include other nonprofit initiatives in and around Nashville.

The meals are served alongside their programming, such as job training, providing attendees with two benefits in one sitting.

The vegetables for all this bounty come in large part from a very robust gardening program that includes five urban gardens.

The goal is to grow what the Food Project is least likely to receive as donations, but it also supports another Nashville Food Project goal: sustainability.

“Community members growing their own food get training and access to land, tools and seeds,” Quinn says.

“We also work with the Center for Refugees and Immigrants of Tennessee on a more rigorous gardening commitment, with the produce going to market and earning them some money.

“Many of these immigrants have an agrarian background, and have so much to teach the newer growers.”