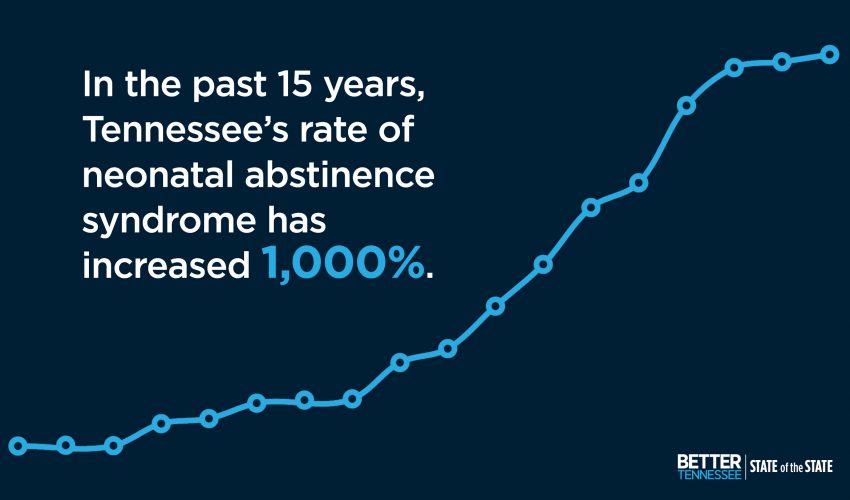

In 2015, Better Tennessee covered the growing problem of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) — when babies exposed to opioids or other drugs in the womb are born dependent on them.

The newborn suffers through withdrawal from the drug soon after birth, a painful process that can last from one week to six months.

The numbers on NAS births in East Tennessee were extremely high, and providers in the area, including Dayspring Family Health, were finding ways to deal with the crisis.

Since the article was published, the opioid problem has been recognized nationally, and medical protocols for expectant mothers and dependent babies have been more clearly established.

We recently spoke to Dr. Cathleen Suto, OB/GYN, who heads up Dayspring Family Health’s initiatives. She talked to us about addressing opioid use during pregnancy, the prevalence of the problem and the glimmers of hope she sees as the facility treats its patients.

Q&A

Better Tennessee: What, if anything, has changed in the last two years in your area regarding NAS and opioid abuse?

Dr. Suto: It is definitely still a big problem in Campbell County and it is not going away. Earlier this year the CDC put out a report saying that Campbell County is #3 in the country for number of opioid prescriptions per capita. Unfortunately for us, that translates into very high rates of NAS. We really have not seen those numbers go down since you spoke to us last.

It would be hard to find any family here not affected in some way by it. We see so many families now with grandparents or great-grandparents raising children because of opioid use disorder. A lot of people associate substance abuse with poverty, but we see it affecting nurses and teachers and pretty much every type of person who lives in the area.

It affects everybody.

What has changed is a shift in the exposure sources for NAS. Now the majority of cases are due to medication-assisted treatments for addiction during pregnancy — buprenorphine, usually. In some ways that is good because it means that more moms using opioids are becoming engaged in prenatal care during their pregnancies.

BT: What kind of help do opioid-using expectant mothers get at Dayspring?

Dr. Suto: We have really changed course in how we approach the problem. We are more focused on outpatient-based addiction treatment now and are able to offer more comprehensive care for moms with opioid use disorders.

In addition to providing prenatal care, we also have integrated behavioral health in place in the clinic, and I offer medication-assisted treatment for patients during their pregnancy and after they deliver.

While I treat these patients during their pregnancy, some of our other providers may treat their family members. By offering Vivitrol, monthly Naloxone injections that treat opioid dependence to them, there is help to improve the environment in the household. I think that’s made a big difference in the long-term health of our families.

Our family medicine providers take care of the babies after delivery, and now we also have developmental specialists from the University of Tennessee who come in to see our babies with a NAS diagnosis. They will follow up with those babies for up to three years.

Click the photo to read about a similar program at Susannah's House, where new mothers like Meghan Denney found peace after years of drug addiction.

BT: Where do you see room for improvement in reducing incidences of NAS?

Dr. Suto: One of the big components to preventing NAS is to prevent unintended pregnancies. Close to 90 percent of the pregnancies in women with opioid use disorders are unintended, according to studies.

So, improving access to long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for patients is key.

Also, 85 percent of the women who are prescribed opioids are not prescribed contraception.

We have opportunities there for primary prevention of NAS if prescribers of opioids and of opioid agonist therapy (medical treatment for addiction) address the issue with their patients.

Is there anything you see that seems encouraging? What are the success stories coming out of this crisis?

Dr. Suto: I think we have changed the way that we are defining success.

A few years ago, our definition of success was a mom who delivers a baby who doesn’t experience NAS. Now we see it as a mom who is engaged in prenatal care, one who is engaged in addiction counseling, is attending parenting classes and, ultimately, one who is able to keep her baby and remain engaged in treatment after delivery.

We are focused on the long-term health and success of our patients and their families.

I have seen more moms deliver and keep custody of their babies and remain in treatment after delivery. The biggest successes are when we are able to get other family members into treatment as well.

Click the image above to read more about neonatal abstinence syndrome in Tennessee.